Help us create an Environmental Health APPG

Join our campaign by urging your local MP to support the formation of an All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on environmental health.

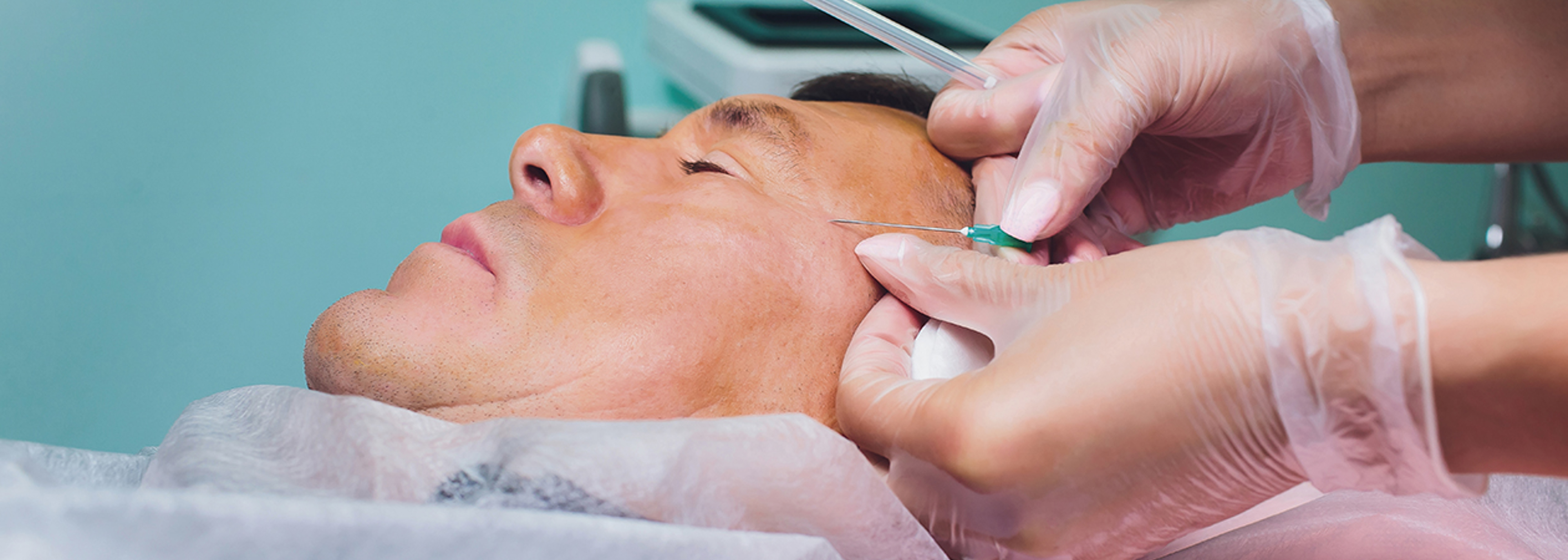

The regulatory regime is woefully under-equipped for controlling the cosmetics treatment market, but calls for change have been heard.

Help us create an Environmental Health APPG

Join our campaign by urging your local MP to support the formation of an All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on environmental health.