Looking for a new role in environmental health?

Whether you're just starting out or ready for your next step, EHN Jobs connects you with the latest opportunities in environmental health across the UK.

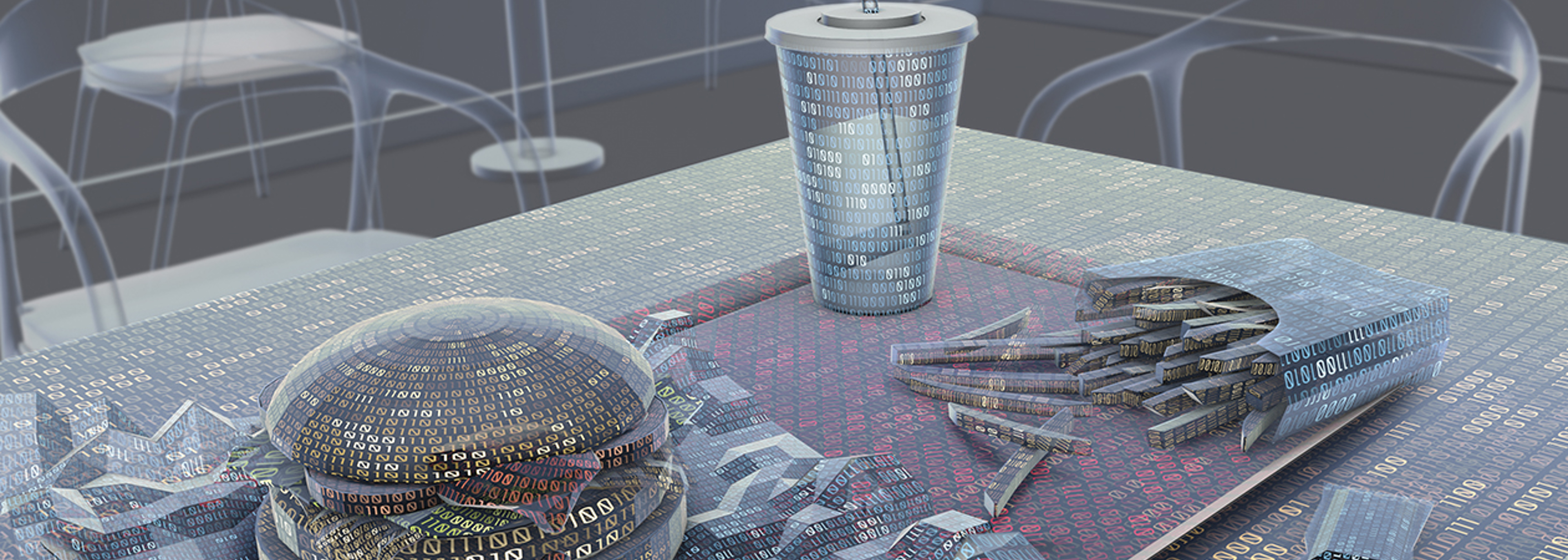

Examples from the world of air quality monitoring and food safety of the power of information – and the challenges still to overcome.

Looking for a new role in environmental health?

Whether you're just starting out or ready for your next step, EHN Jobs connects you with the latest opportunities in environmental health across the UK.